Description

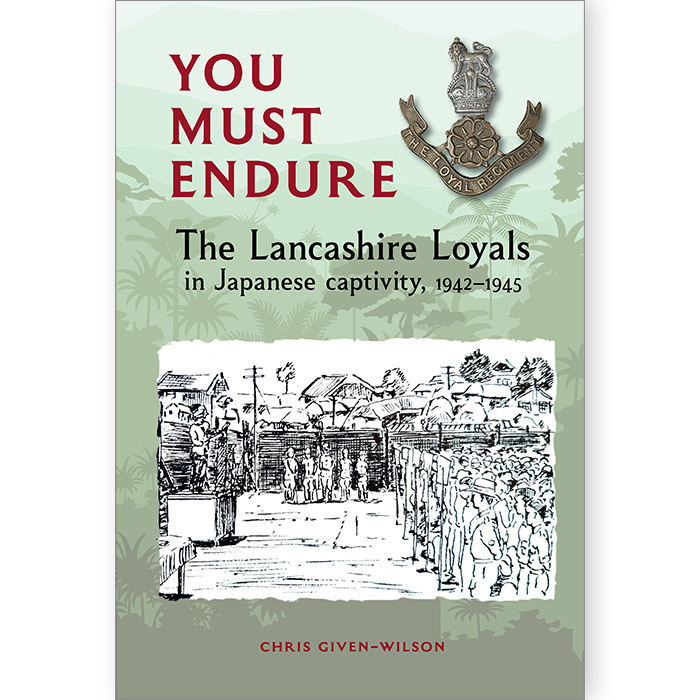

The time was 7.40 p.m., the date 15 February 1942. The light was fading fast, the Allied forces were encircled, and the bombardment was relentless, as Singapore fell to the Japanese.

Discarding their weapons, the Lancashire Loyals quietly withdrew to their quarters, where they ‘composed themselves as best they could for the silent ordeal of the night, numbed and galled by the bitterness of enforced surrender’. So began three and half years of incarceration at Keijo POW camp in Korea.

This is the previously untold story of the brave Lancastrians who endured, told by Chris Given-Wilson, whose father was one of those captured. It is a story of brutality, starvation and disease, but also one of survival, determination and creativity. Among the many ways the prisoners sought to keep their spirits up were the staging of surprisingly sophisticated shows, complete with Gloria d’Earie, the resident female impersonator; the growing of fresh vegetables to improve their health; and the regular publication of Nor Iron Bars (co-edited by the author’s father), with its satirical portrayals of camp life. Copies of this banned journal were successfully concealed from the guards to be smuggled home, and can be seen at the Lancashire Infantry Museum.

Chris Given-Wilson writes with warmth and humour, to reveal both the best and the worst of human nature. This book should be read by everyone, but perhaps especially all proud Lancastrians.

- Author: Chris Given-Wilson

- ISBN: 978-1-91083-7351

- Binding: paperback

- Pages: 160

- Illustrations: colour, throughout

- Publication date: 16 October 2021

Paul Carter, British Association for Local History –

The experiences of Allied prisoners of war at the hands of their brutal Japanese captors have been well-documented in texts and popular media. The building of the Death Railway between Thailand and Burma in 1942-3 and its representation in ‘The Bridge on the River Kwai’ remains one of the defining images of this part of the Second World War. Even so, accounts of the war in the Pacific are vastly outnumbered by those centred on Europe and Britain’s fight at home, even though the highly prized British Empire was at greater threat from Japan. It’s a rare treat, therefore, to encounter a book with such colour and detail as You Must Endure. The book tells the story of the 2nd Battalion, the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, from the events leading up to their capture in Singapore to their subsequent imprisonment in Keijo (the Japanese name for Seoul) and liberation three years later. The author’s father, 2nd Lieutenant Patrick ‘Paddy’ Given-Wilson was one of those imprisoned at Keijo. He, with two other British POWS, Capt. John Turner and Lt. Tom Henling Wade, edited and illustrated a magazine entitled Nor Iron Bars, comprising much of the primary source material for You Must Endure. The magazines, hidden from the Japanese captors, were safely transported back to Britain at the end of the war and are now housed at the Lancashire Infantry Museum.

The fall of Singapore was a catastrophe for the Allies and the book provides a clear and well-illustrated account of the Japanese ‘Blitzkrieg’ tactics of push and encircle through Malaya, which ended in a final stand at the southern tip of the peninsula. Initially the captured were held in Singapore, many at the British military base of Changi. It wasn’t just the Allies who suffered: the Japanese executed between 5,000 and 70,000 native Singaporeans, their bodies left for the POWs to retrieve and bury in mass graves. It was at Changi where the first five issues of Nor Iron Bars were produced to alleviate boredom and ‘occupy the minds of a few individuals’. Those individuals were the thirty or so officers of the Loyals, a point which is returned to several times in the book. The content matter often reflected the humour and concerns of the officers and rarely that of the larger number of ordinary ranks.

The time at Changi was considered deceptively peaceful, with dysentery the biggest danger for the men, but the Loyals would soon experience some tougher times in their transfer to Korea. The voyage from Singapore, on an overcrowded steamer, marked the most perilous period of the prisoners’ captivity. Japanese POW transports looked no different to troopships or supply vessels, and many were attacked by the United States aircraft and submarines patrolling the seas. It is believed that 40 per cent of the 50,000 Allied prisoners transported by Japanese ship between 1942 and 1945 died at sea, many from friendly fire. In one account, a steamer was torpedoed by a US submarine: 700 Japanese army personnel were on board, but unknown to the Americans, so were 1800 British and Canadian prisoners. The Japanese evacuated the ship, but not before they battened down the hatches to the holds containing the POWs.

The Loyals did reach Korea relatively unscathed, although in subsequent weeks, some men were lost as a result of disease and malnutrition. As the POWs settled into life at Keijo they learnt the differences in culture between East and West. The camp commander, Col. Noguchi, was a stickler for protocol but not as unreasonable as some counterparts in other camps. The prisoners were made to bow to 15 degrees, and failure to take roll call in Japanese resulted in being slapped. Initially Keijo was a show camp for the Japanese, which meant conditions were easier and there was a higher proportion of officers. It is well known that rations were limited in Japanese camps and the Keijo POWs did continue to suffer from malnutrition. What is less understood is that their captors survived on similar rations, and both groups were certainly better fed than the Korean peasants, a fact which goes some way to explaining the lack of sympathy from the Japanese. The prisoners were even given flour to make their own bread and some land to grow crops. Although the Japanese did not celebrate Christmas, they did respect festivals and the prisoners enjoyed extra rations and food parcels for Christmas Day.

The cordial relationship between the camp officers and their Allied counterparts did mean the prisoners at Keijo were not subjected to the same harshness as those at other Japanese camps. There were beatings by a few of the guards, a lack of medication and poor care, but primarily the prisoners suffered from the extremes of weather, with high heat and freezing cold. The Red Cross did arrange visits on occasions but in one case the representative spent just a few minutes at the camp and was later found to be a Japanese resident!

As the war drew to a close and Japanese defeat seemed more likely, the local Koreans became more brazen in their help and support of the POWs. Unlike in other camps, where there were reports of mass executions of prisoners, the Japanese at Keijo maintained control, with a mutual respect for their captives. After their eventual liberation, the Loyals returned home in October 1945.The author reflects on the history leading up to the war and the Japanese attitude to the colonial powers all around them. While many were rightfully convicted for horrific war crimes, was it such a defeat for the Japanese after all? In the post-war years, those countries under colonial rule gained independence. It was, in Japanese eyes, a battle of empires, not of states. This insight, combined with the details taken from Nor Iron Bars makes You Must Endure a fascinating read. Indeed, many of the book’s illustrations are artwork and drawings taken from Nor Iron Bars and few copies of family letters.